What I like most about offseason mass training is its simplicity. You just train hard and heavy while following the "see-food" diet.

Getting ripped, however, is a helluva lot more complicated. You not only have to start watching what you eat, you must also consume fewer calories each day than you're burning—but not too many more. And of course, that combination brings about hunger and food cravings.

Your ratio of macronutrients also changes to limit muscle catabolism during this period. Your training ramps up in intensity to raise your metabolism for the duration of your workout, so you're spending less time on your butt between sets. You may likely have to include cardio, perhaps in the form of high-intensity interval training (HIIT), to further increase the gap between calories in and calories burned. Supplements that help with energy, focus, and fat loss become even more beneficial as your body becomes increasingly fatigued. And with all that work, you need a recovery strategy that's better than "I'll catch up with my sleep over the weekend."

All that extra work pays big dividends come contest time or when you pull your shirt off at the beach, though. You will have separated yourself from those still following that simple offseason program.

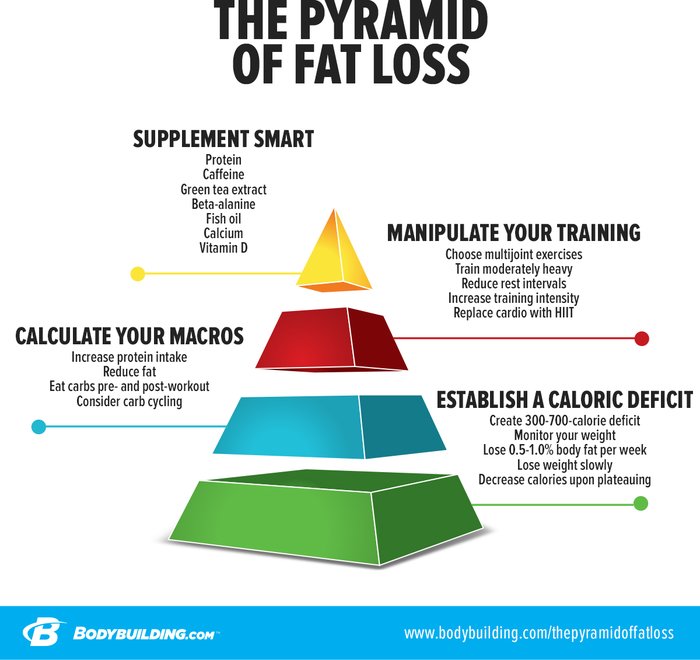

To help sort through the most critical factors and provide a few strategies to get you started, we've devised a fat-loss pyramid.

Pyramids, not unlike the foundation of a house, are built from the ground up. The bottom level is the most critical, because it must support everything above it. Nail the bottom tier of the pyramid, or all the work you do on top will have been for naught.

Level 1. Establish A Caloric Deficit

"To lose body fat, you have to expend more energy than you take in," says

EAS spokesperson and amateur bodybuilder Steven Lopez. "If you're in a surplus, you'll gain weight; if you're taking in about what you're burning, you won't!"

The first step to setting up a diet is to determine how many calories (or macros) you need to place yourself in a calorie deficit. A popular and convenient approach is to start with an

online fitness calculator that estimates total daily energy expenditure (TDEE). This simple-to-use calculator requires you to provide a few pieces of basic information about your size, exercise habits, and goals (choose "Fat Loss" to match your goal for this program). It then estimates the number of calories (and macros) needed per day to help you reach that goal.

Exercise increases the number of calories you burn each day.

The caloric deficit is roughly 300-700 calories a day, depending on your body weight. This will allow you to lose weight at a safe rate of about 0.5-1.5 pounds per week.

Because the numbers computed are all estimates, monitor your results over the next 7-10 days by weighing yourself every other day at the same time.

"If your weight isn't trending downward, you're not in a deficit," says Paul Salter, MS, RD, Bodybuilding.com's nutrition editor. "However, if you drop a few pounds in the first 7-10 days (partly because of water loss that first week), you're right where you want to be. Continue with this current plan until your weight begins to plateau. Once you plateau, further reduce your calories by 10-20 percent to recreate a calorie deficit. Your goal is to lose 0.5-1.0 percent of your body weight per week. This amounts to 1-2 pounds per week for a 200-pound individual. Losing weight any faster than this significantly increases your risk of muscle loss and the likelihood that you'll derail your dieting efforts because you're being too strict."

Level 2. Calculate Your Macros

"Following the correct macro breakdown for your specific goals is just as important [as a caloric deficit]," says Lopez. "If you're trying to get ripped, the goal is always to lose fat while maintaining muscle mass. Tracking your macros as well as your calories will ensure you're continuing to make progress."

The macronutrient calculator in Level 1 gave you a starting point for macros. If you click between "Maintenance" and "Fat Loss," you'll notice the calories drop significantly in fat-loss mode. No surprise there.

The carbs and fat also drop, but not your recommended protein intake. "Protein's importance isn't limited to people trying to gain size; if you're dieting, protein should become your new best friend," says Salter. "Protein slows down digestion and triggers the release of appetite-suppressing hormones—talk about a defense against hunger and cravings! And consuming sub-optimal protein levels may result in your hard-earned muscle mass being used as energy."

Research suggests consuming 0.8-1.25 grams of protein per pound of body weight may be optimal for minimizing muscle loss during a diet, particularly during a low-calorie or prolonged diet.[1,2] Salter urges you to remember that the additional bump in protein should not come at the expense of knocking yourself out of a caloric deficit. You must compensate by reducing carbs, fat, or a combination of both to maintain your deficit.

To date, you may have avoided counting macros and calories, but winging it here can cause huge daily caloric fluctuations. "It's absolutely smarter, at least initially, to track exactly how many calories you're taking in," advises Lopez. "This will allow you to cut or adjust macros and calories when needed to reach your fat-loss goal. Counting calories is an important tool to help you lose body fat."

"A diet consisting of whole, unprocessed foods is the place to start your fat-loss journey [in the kitchen]," says Krissy Kendall, PhD, CISSN, science editor at Bodybuilding.com. "That helps ensure you're getting not only your crucial macronutrients, but also the micronutrients your body demands for optimal performance and recovery."

When restricting calories, eating enough protein becomes even more important.

Many dieters mistakenly take the hatchet to their carbohydrate intake. "But there are more horror stories with this approach than success stories," Salter notes. "Extended low- or no-carb diets tend to depress metabolism. They also can rob your workouts of much-needed energy."

To maximize gym performance, eat a majority of each day's carbs during your pre- and post-workout meals.

"An additional approach to consider is carb cycling," Salter adds. "In its basic form, carb cycling involves manipulating the amount of carbs you consume each day in relation to your training. For example, consider eating a higher amount on training days and fewer on nontraining days. This will further help ensure you're fueled appropriately for training."

Don't forget that the type of carbs is also important. "It all has to do with the insulin response and your blood-sugar levels," says Lopez. "Simple carbs will cause a rapid increase in blood sugar and are more likely to be stored as fat unless you restrict them to pre- and post-workout." Outside of those windows, too many simple carbs can set you up for an energy crash soon after consumption.

"Instead, opt for complex carbs that digest and are absorbed more slowly. The smaller impact on blood glucose and insulin will provide steady energy in the hours to come while helping to keep your appetite in check."

Level 3. Manipulate Your Training

Once you've dialed in your nutrition to better suit fat loss, you need to do the same when it comes to training. After all, a mass workout isn't ideally suited for getting you lean. Let's look at some ways to decrease fat while minimizing muscle loss.

Favor multijoint exercises over single-joint ones. This is fairly common advice, but some workouts, especially for shoulders or arms, depend heavily on single-joint moves. Because you recruit a greater number of muscle groups when doing multijoint exercises and can push more weight, they'll do a better job of boosting your metabolism. Plus, they better trigger a cascade of favorable anabolic hormones. This can greatly affect muscle growth and fat burning.

Use fairly heavy loads while shortening your rest intervals. Going light for high reps may seem like more work, but it doesn't do much for the fast-twitch muscle fibers. Fast-twitch fibers are the most prone to growth via resistance training and may be subject to atrophy when they are no longer targeted. Research shows that training with heavier weight (around 6RM) helps to raise metabolism higher and for longer than using lighter loads.[3]

Keep your work-to-rest ratio about 1-to-1. "You can best maintain strength by sticking with 8-12 reps and maintaining high-volume work, says

Nikki Walter, a fitness model and EAS spokesperson. "Also, improve your conditioning and fat burning by doing more activity between sets or simply reducing the length of your rest intervals." Your body does adapt to this protocol, but it will be challenging at first.

You know you have to burn more calories to get lean, but lengthening your workout isn't the answer when on a reduced-calorie diet. Catabolic hormones like cortisol can start to rise after about an hour of higher-intensity training.[4] Instead, increase the volume by using intensity principles such as rest-pause, dropsets, supersets, cluster sets,

density training, or even a technique like

FST-7 on your final exercise.

The goal here is to do more work in less time, increasing the intensity of your workout to improve your conditioning and elevate excess post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC). That simply means you burn an increased number of calories long after your workout as your metabolism slowly returns to equilibrium. This process can take up to 24 hours.

Adding cardio can increase the gap between calories consumed and calories burned.

Even with all that work, your daily gap between calories in and calories burned may still not be wide enough to promote fat loss. Since you've already drawn a line on the length of your weight workouts, let's consider how cardio activity can push you over the top. Fortunately, research has verified a more time-efficient protocol than sitting on a bike or treadmill for an hour; it's called

high-interval intensity training (HIIT).

HIIT involves cycling periods of high-intensity work with easier ones for recovery, and you repeat those back and forth over the course of 20-25 minutes. Because of its effect on metabolism and EPOC, it can help you burn more calories and fat in less time than steady-state.

"I find HIIT especially useful for people who are tight on time and still want to get cardio work in," says Walter. "HIIT is superior for raising metabolism and decreasing body fat; it's a time-efficient method for burning calories while also improving your conditioning and heart health."

Level 4. Supplement For Fat Loss And Energy

It can be especially hard to recover adequately, meet your macros, and train hard when cutting. This is where a

quality supplement can help.

"If your goal is to get shredded, a

quality whey protein should be a top priority," says Kendall. Besides its effects on stimulating muscle protein synthesis and helping your muscles repair and recover after a tough workout, increased protein consumption is associated with higher rates of satiety (feeling of fullness) and thermogenesis (energy expenditure).[5]

Caffeine is the foundation of an

effective pre-workout supplement. Studies have shown caffeine-containing supplements may improve the rate of fat breakdown and reduce perceived exertion during exercise.[6,7] Also consider green tea extract, or more specifically EGCG, the primary ingredient in green tea extract responsible for boosting metabolic rate.[8] Taken together, the combination of EGCG and caffeine have been shown to be more effective when it comes to fat loss and increased energy.[9]

Energy levels can lag when following a calorie-restricted diet. That's where supplements can help.

Certain types of fat—like fish oil—can help you lose body fat while increasing fat-free mass.[10,11] Supplementing with omega-3s has actually been shown to help your body burn more fat while also increasing rates of protein synthesis and muscle gain.[12]

Because of the increased intensity and density of fat-loss workouts, Kendall notes that hydrogen ions accumulate, lowering your blood's pH levels while contributing to fatigue. Carnosine, a protein building block that beta-alanine helps to produce in your body, serves to buffer hydrogen ions. This allows you to work at higher intensities for longer periods of time.[13]

Additional supplements to consider include calcium and vitamin D. A calcium-rich diet has been shown to increase rates of fat oxidation, reduce fat absorption, and help control appetite, while vitamin D intake is related to lower levels of adiposity and improved metabolic health.[14-17]

Achieving fat loss requires important foundational strategies, but your chances of success improve when you address all levels of the fat-loss pyramid. And if at any time you decide to switch goals and build muscle, check out our

Pyramid of Muscle-Building!

References

- Butterfield, G. E. (1987). Whole-body protein utilization in humans. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 19(5 Suppl), S157-65.

- Phillips, S. M., & Van Loon, L. J. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. Journal of sports sciences, 29(sup1), S29-S38.

- Børsheim, E., & Bahr, R. (2003). Effect of exercise intensity, duration and mode on post-exercise oxygen consumption. Sports Medicine, 33(14), 1037-1060.

- Hill, E. E., Zack, E., Battaglini, C., Viru, M., Viru, A., & Hackney, A. C. (2008). Exercise and circulating cortisol levels: the intensity threshold effect. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 31(7), 587-591.

- Frestedt, J. L., Zenk, J. L., Kuskowski, M. A., Ward, L. S., & Bastian, E. D. (2008). A whey-protein supplement increases fat loss and spares lean muscle in obese subjects: a randomized human clinical study. Nutrition & Metabolism, 5(1), 8.

- Costill, D. L., Dalsky, G. P., & Fink, W. J. (1977). Effects of caffeine ingestion on metabolismand exercise performance. Medicine and Science in Sports, 10(3), 155-158.

- Arciero, P. J., Bougopoulos, C. L., Nindl, B. C., & Benowitz, N. L. (2000). Influence of age on the thermic response to caffeine in women. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, 49(1), 101-107.

- Nagao, T., Hase, T., & Tokimitsu, I. (2007). A green tea extract high in catechins reduces body fat and cardiovascular risks in humans. Obesity, 15(6), 1473-1483.

- Thielecke, F., Rahn, G., Böhnke, J., Adams, F., Birkenfeld, A. L., Jordan, J., & Boschmann, M. (2010). Epigallocatechin-3-gallate and postprandial fat oxidation in overweight/obese male volunteers: a pilot study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 64(7), 704-713.

- Hill, A. M., Buckley, J. D., Murphy, K. J., & Howe, P. R. C. (2007). Combining fish-oil supplements with regular aerobic exercise improves body composition and cardiovascular disease risk factors. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 85(5), 1267-1274.

- Noreen, E. E., Sass, M. J., Crowe, M. L., Pabon, V. A., Brandauer, J., & Averill, L. K. (2010). Effects of supplemental fish oil on resting metabolic rate, body composition, and salivary cortisol in healthy adults. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 7(1), 31.

- Smith, G. I., Atherton, P., Reeds, D. N., Mohammed, B. S., Rankin, D., Rennie, M. J., & Mittendorfer, B. (2011). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids augment the muscle protein anabolic response to hyperinsulinaemia–hyperaminoacidaemia in healthy young and middle-aged men and women. Clinical Science, 121(6), 267-278.

- Harris, R. C., & Stellingwerff, T. (2013). Effect of beta-alanine supplementation on high-intensity exercise performance.

- Caron‐Jobin, M., Morisset, A. S., Tremblay, A., Huot, C., Légaré, D., & Tchernof, A. (2011). Elevated serum 25 (OH) D concentrations, vitamin D, and calcium intakes are associated with reduced adipocyte size in women. Obesity, 19(7), 1335-1341.

- Sulistyoningrum, D. C., Green, T. J., Lear, S. A., & Devlin, A. M. (2012). Ethnic-specific differences in vitamin D status is associated with adiposity. PloS One, 7(8), e43159.

- Jacqmain, M., Doucet, E., Després, J. P., Bouchard, C., & Tremblay, A. (2003). Calcium intake, body composition, and lipoprotein-lipid concentrations in adults. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 77(6), 1448-1452.

- Gonzalez, A. J., White, E., Kristal, A., & Littman, A. J. (2006). Calcium intake and 10-year weight change in middle-aged adults. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 106(7), 1066-1073.